In Defense of ORMs

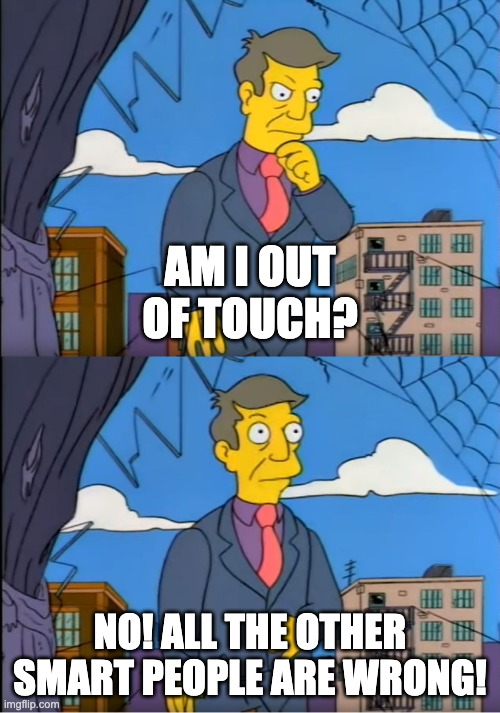

Object Relational Mapping tools are an extremely contentious topic these days. Today, all it takes is for someone to write on a forum or walk up on a speaker stage, proclaim:

Don’t use an ORM - just write SQL

and what follows will be a standing ovation, virtual or in real life.

In my experience, your typical ORM hater is smart, productive and very influential wherever they work. That is why it has taken me so long to figure out whether I disagree with them, or if I am simply too stupid to have come to the same conclusion.

It was not until I heard that at least one more influential programming influencer actually DO see them as valuable that I begin to let myself defend them intellectually.

highly recommended even if you don't end up using it, lots of great & interesting ideas

— htmx.org / CEO of SEO (same thing) (@htmx_org) November 1, 2023

ActiveRecord remains my favorite ORM, very pragmatic, stays out of the way & leverages OO in the right wayhttps://t.co/OIIT10GDiw https://t.co/DyeNU3Qml0

The criticism

The hatred for ORMs is not unfounded. I would never go so far as to say that anyone who says their application became simpler when they tossed it out in favour of just writing SQL strings is lying. Lots and lots of of especially Java shops have been burnt on the JPA/Hibernate stove, and you will hear them complaining about:

- fighting weird, implicit

N+1performance problems - debugging unexpected flushing and cache invalidation behaviours

- never truly understanding the correct combination of annotations to get their many-to-many to work

It is natural that they start to gag when an online guide is suggesting you pick it up “to avoid having to learn or write SQL”. But I feel like the popularized position of rejecting the entire concept of an ORM means throwing out the baby with the bathwater. I contend that the problem with ORMs is not the idea itself, but something else.

The problem

There are a couple of actual large problems with ORMs that I will totally admit.

Use an ORM to not learn SQL

This is a terrible idea. If you are using a relational SQL database, then learning how that SQL database works is key. Gavin King, the creator of Hibernate, even has this to say about Hibernates relationship to its underlying database:

Indeed, systems like Hibernate are intentionally designed as “leaky abstractions” so that it’s possible to easily mix in native SQL where necessary. The leakiness of the ORM abstraction is a feature, not a bug!

ORMs were always meant as a tool to help expressing parts of your database interactions, namely state transitions, while intentially letting you also interact with the database in other ways where raw SQL outperforms the ORM in ease-of-use.

Gavin later in the same comment goes on to say:

I speculate that the problem is not that ORM gets in the way of using SQL, it’s rather that so many Java/C#/Ruby/Python/JavaScript developers don’t have a strong enough knowledge of, or aren’t sufficiently comfortable with, relational databases and the relational model. That is emphatically not the fault of ORM!

I find this a little less convincing. If anything, the design of the tools are often going to encourage a specific kind of usage. If we are in a place where people frequently use ORMs in a way they were never designed to be used or, then it can of course very well be that the tool itself is not very self explanatory.

I suspect there might be another culprit, however…

Hibernate

Most of the ORM complaints I have heard come from people fighting with Hibernate specifically. I have spent my time working mostly on the JVM, which means it could just be a sampling bias, but I rarely hear people complain about Rails’ ActiveRecord the way they do about JPA/Hibernate.

I respect this criticism. Hibernate is by no means the most obvious way to implement an ORM. Any ORM is going to have a layer of “magic” between the code and the underlying SQL, but said magic comes in different flavors.

The way this magic works in Hibernate/JPA is that any so-called @Entity in Hibernate is “observed” from the side by an EntityManager, where the EntityManager reads the annotations of the entity class and attaches the appropriate behaviour. This model deeply obfuscates what actually happens in the entity lifecycle, as all the “what actually happens” stuff is tossed far away from the actual entity definition.

It doesn’t help that Hibernate is perhaps a bit TOO flexible when it comes to defining relationships. Entity relationships can be both eager and lazy, and can have intricate “cascade” rulesets, which define whether creating/updating/deleting one entity should automatically trigger a similar write on another. It also has both @OneToMany and @ElementCollection annotations, which both are some kind of one-to-many, and I myself don’t really fully understand the difference.

The combination of all these attributes, together with the fact that all of them are “operated from afar” by an EntityManager, means that it is hard to create some kind of intuition regarding how it actually all works. It is of course extremely well documented (otherwise it would never work at all), but good documentation can’t compensate for an unintuitive model.

ActiveRecord on the other hand, and my recent JVM favorite Kotlin Exposed, are both inheritance based models, where your ORM data models inherit from some base class, and interacting with the state of your object means said changes propagating down to some underlying mechanism. In Kotlin Exposed, the “magic” that happens in my ORM classes can be found by simply using “go to definition” in my IDE. Inheritance gets a bad rap these days, but it is in fact a pretty appealing choice for building a simple 80/20 ORM.

Spring Data JPA

The dominant application building framework on the JVM is Spring, and more recently Spring Boot. Boot specifically (inspired by Rails) is a “convention over configuration” library which helps you set up a “sane defaults” configuration to quickly get going without having to make too many choices upfront.

One particularly fateful, cursed decision made early in Spring is to make JPA and Hibernate its default, and in many ways only, batteries-included library for working with the database. This is unfortunate, because it forces people to opt-out of using JPA to interact with the database, rather than opting-in to using it once they are convinced that an ORM could work for them in their domain.

In Spring Data JPA specifically, not only are you often using Hibernate, but Hibernate is also encapsulated inside the Domain Driven Design-inspired repository-pattern of Spring Data - which hides the EntityManager entirely. So not only are you dealing with the already quite obscure EntityManager, but now all of that hides behind another layer of repository interfaces with proxy-implementations generated at runtime.

I don’t think the desire to create a happy-path setup for database interaction is a bad idea, but when it comes in the form of Spring Data and JPA/Hibernate, I admit one has good reason to be disappointed.

When can ORMs shine?

ORMs let you express several database tables as a single object graph. For many complex OLTP systems, the ability to encapsulate state transitions underneat a single object is a real help.

Imagine you have an model that encapsulates a complaint made by a customer to some company. Imagine one crucial state transition of this complaint is “closing” it, when it is considered handled by your support staff. In a real world application, changes like these are usually non-trivial. Let us imagine that we have the following things that need to happen in our database:

- The

complaintneeds to be marked asclosed_at = now() - A

complaint_eventneeds to be inserted expressing that it was closed - If there are any

complaint_taskentries that are still unresolved, we wish to add anothercomplaint_eventexpressing that - If there are any

complaint_taskentries marked asescalated, we reject closing altogether

Using some hypothetical ORM, the code would typically end up looking like this (using Kotlin):

class Complaint {

private var closedAt: Instant? = null

private val tasks: OneToMany<ComplaintTask> = OneToMany()

private val events: OneToMany<ComplaintEvent> = OneToMany()

fun close() {

val hasEscalated = tasks.any { it.isEscalated }

if (hasEscalated) throw IllegalStateException("Can't close complaint with escalated tasks")

val hasUnresolvedTasks = tasks.any { !it.isResolved }

if (hasUnresolvedTasks) {

events += ComplaintEvent(complaint = this, description = "Complaint closed with unresolved tasks")

}

events += ComplaintEvent(complaint = this, description = "Complaint closed")

closedAt = Instant.now()

}

}

in this model, all the rules related to closing are protected inside this function. The pattern, when used like this, encourages expressing multi-table state transitions and invariants deep down on the “database type” itself, right next to the database column declarations. This achieves really high levels of Locality of Behaviour.

Without the use of an ORM, the same code ends to look something like this…

class ComplaintService(

// dao == "data access object"

private val dao: ComplaintDao

) {

fun closeComplaint(id: String) {

val tasks = dao.findTasksByComplaintId(id)

val hasEscalated = tasks.any { it.isEscalated }

if (hasEscalated) throw IllegalStateException("Can't close complaint with escalated tasks")

val hasUnresolvedTasks = tasks.any { !it.isResolved }

if (hasUnresolvedTasks) {

dao.addEvent(complaintId = id, description = "Complaint closed with unresolved tasks")

}

dao.addEvent(complaintId = id, description = "Complaint closed")

dao.updateComplaintSetClosedAt(complaintId = id, closedAt = Instant.now())

}

}

class ComplaintDao(

private val database: Database

) {

fun findTasksByComplaintId(complaintId: String): List<ComplaintTask> {

return database

.query("SELECT * FROM complaint_tasks WHERE complaint_id = ?", complaintId)

.convertTo<List<ComplaintTask>>()

}

fun addEvent(complaintId: String, description: String) {

database

.update("INSERT INTO complaint_event (complaint_id, description) VALUES (?, ?)", complaintId, description)

}

fun updateComplaintSetClosedAt(complaintId: String, closedAt: Instant) {

database

.update("UPDATE complaint_event SET closed_at = ? WHERE complaint_d = ?", closedAt, complaintId)

}

}

… if you are lucky. If you instead work with people who would rather write DAO functions for hasEscalatedTasks or hasUnresolvedTasks, then you will have even more specialized methods on he second class.

In a real world application, I tend to see that the latter “just write SQL” pattern tends to come in two shapes:

- Either whatever code is run inside the Service just executes SQL directly…

- This in order to avoid excessive layering (which I am a fan of!)

- … or all common queries and updates are placed in a single DAO type like upstairs

- This in order to have reusable database interaction functions

Both of these styles fail to capture the strengths of the original ORM one. Splitting things up in more layers can cause the “separation of concerns problem” where code must be read across multiple files to be understood. The DAO facades tend to get so big and hyper-specialized that you often find yourself always adding new functions for anything you write, creating an ocean of functions that have all their filters and joins in their name like findAllTasksWithOutcomeAndBlockersWhereIsNotDeletedAndComplaintId.

But most importantly, the ORM pattern creates a single place where you more or less HAVE to add state changes to, which means you also need to review how your addition or change affects the other rules of said type. In a “just write SQL” world, it is not uncommon for a new addition to the code to simply ignore any other attempts at controlling the lifecyle of data by just adding new update functions from the side. None of these patterns make either possible or impossible, but ORMs definitely is stronger at co-locating the state itself and its changes.

What about querying?

Notice how I did not mention reading data a single time in the previous section. That is on purpose. ORMs are pretty convenient when doing basic reading too. If most of your system can be expressed in terms of reading an updating singular “objects”, then using an ORM for querying works splendidly as well.

But virtually all people who hate ORMs with a passion can recall debugging a performance problem where they fetched multiple objects from the database using an ORM, and tried their best to query them efficiently or maybe updating some of them in batch. Suddenly, what is trivial when “just writing SQL” becomes nearly impossible with the ORM. That’s true - because ORMs are not designed to perform large, complex querying or batch processing.

But Fredrik, quite often one has to do that - doesn’t that mean ORMs are a bad fit almost always?

I mean, that’s exactly why ORMs are designed as leaky abstractions by design. If you need to make complex queries, then just bypass the ORM. That’s the whole point. ORMs are there to help you express complex changes of the data, while still letting you operate freely with the database on the side. Every single ORM I have encountered bakes in raw SQL access in its public API, without having to set up a database connection from the side.

In the Complaint example of the previous section, it would make perfect sense to:

- Use the ORM for interacting and working with a single complaint in your system

- Use SQL to generate charts and reports for open complaints

In sum

If you find yourself in a business domain where complex state transitions on singular types are rare, then it makes perfect sense to never even consider an ORM. If you deal with huge imports of mostly immutable data, batch processing of information or running complex queries on large datasets using Hibernate, then yes you are going to have a bad time.

But a lot of us actually DO make complex state transitions on singular data graphs. And some of us do use ORMs, and we are doing fine.

Also, if you just hate all ORMs with a passion, then that’s fine. Enjoy your findUnresolvedPaymentsWithCustomerDataAndAccountInformationFromLastMonth functions!