Kotlin extension functions are (mostly) bad

Here we go! Clickbait headline right out the gate. There is nothing inherently wrong with how extension functions in Kotlin work or behave. However, I find we can talk about one aspect of Kotlin extension functions as a proxy for what I consider to be a software development malpractice. One day I aspire to find the words to write the big blog post of my dreams on the underlying topic - but for now this tiny little Kotlin thing will do.

Before we go further, let me quickly demonstrate what we’re talking about. Extension functions are a neat little syntactic trick baked on top of an ugly, underlying JVM signature that makes for a nicer call site. This means you can do something like this:

// instead of this...

object AddressUtil {

fun prettyString(address: Address): String {

return "${address.street} ${address.streetNumber}, ${address.zipCode}"

}

}

// ... with this butt-ugly call-site...

val string = AddressUtil.prettyString(address)

// ... you can have this...

fun Address.prettyString(): String {

return "${this.street} ${this.streetNumber}, ${this.zipCode}"

}

// ... so pretty! It looks like the function is actually part of the Address type

val string = address.prettyString()

But this neat little syntactic trick has opened more than one of Pandora’s little boxes. There are obvious pitfalls like:

fun String.toLocalDate(): LocalDate = LocalDate.parse(this)

// wtf - it's so weird for `.toLocalDate()` to show up on auto-complete for ALL strings

"zuck@facebook.com".toLocalDate()

But today I am not interested in small, ugly things like being able to parse Mark Zuckerberg’s email address into a date object. Instead I hope to persuade you that there is a larger problem that causes real damage to readability.

Pandora’s by far least favorite box

The following insight came to me when I was visiting KotlinConf this year, and I saw a talk related to library API design in Kotlin. There was this one bit in the middle of it, a comment made by the presenter, that triggered something in me. The full quote:

You can also add [Kotlin Extension Functions] to types that you own… And I also like to do that because it makes a clear separation between what is core in your class, and what is not. Another way to think about it is that you have classes for your data, and then you have extension functions for your code.

After I saw it said explicitly, it dawned on me that I see this pattern a lot in my professional life.

// people seem to prefer this

class Person {

// this declaration only has the state

var address: Address? = null

}

// and then place operations on said state elsewhere - sometimes in a SEPARATE FILE

fun Person.moveTo(newAddress: Address) {

this.address = newAddress

}

// instead of just...

class Person {

var address: Address? = null

// boo - methods?! what is this, Java????

fun moveTo(newAddress: Address) {

this.address = newAddress

}

}

When I talked to some proponents of this pattern, they tell me that what they like about it is that it becomes clean. The state is declared in one place, and the state transitions in another. This allegedly makes the code more tidy instead of everything being jumbled together. They point to the declaration of the type itself and all its state, and the pristine aesthetics of having only declared a block that resembles a struct in C.

Let us look a bit closer at the pros and cons.

The “benefits”

It is not a particularly hot or contrarian take to say that when people say “clean” what they actually mean is “code I like”. Most developers agree that it is of supreme importance that code is easy to read. Some people, of course, will make the case that code being “clean” IS what makes it readable. At the same time, the only way to actually prove that said “clean” code is actually easy to read would be to write the same program twice; once strictly with the pattern and once without, and then have several third parties try to interpret the code and somehow grade their ability to understand it.

The proposed benefits of this split is that it makes sense to only look at a type as what it contains, and filter away everything about what it does. This is meant to be less distracting when you simply want to know what properties something has, and vice versa.

Now, you might expect me to say that splitting up state and state transitions in separate files and motivating it by saying that it is “tidy”, “clean” or “nice” is doing something without real, provable benefits. That’s not enough however. I would go as far as saying that it is an emotional attachment to something that has glaringly obvious drawbacks.

The drawbacks

Splitting up state and state transitions, if you CAN keep them together, does not make any sense. It is a clear step away from writing cohesive code. Cohesion refers to the practice of squeezing things together that belong together - I struggle to find anything quite as cohesive as the state of a type and the procedures one can use to manipulate said state. They are always relevant together.

If you put all your code for a type in one place, then a single jump in your IDE takes you to all the things that type does. If you split them up, now you have to read multiple files at once to figure out the myriad ways the type can be interacted with.

Also, in this specific case, the only way for an extension function to actually mutate any state is for that state to be publicly mutable, undermining any attempt at information hiding or protection of invariants.

Programmers are obsessed with splitting things up

Imagine being a home decorator who thinks bathrooms tend to be over-furnished. There is simply too much going on in the bathroom. But then this professional has an epiphany! If we simply put the sink and everything that goes with it in another room, we will have a super clean toilet-only space, and a pristine sink-only space. Genius! Except… you know…

There is simply too much focus in software development on how to split things up. Be it modules, libraries, micro-services or whatever. I personally feel like the quest for separation starts in the wrong end. We shouldn’t be looking to find what things to spread out, we should search for what we squeeze together. Few things are as satisfying as when you want to change or extend a program, and quickly discover that all the things I need to touch are right here. After figuring out what parts to collapse into cohesive bits, the separation reveals itself as whatever is left.

Intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second

In his book The Righteous Mind, psychology professor Jonathan Haidt lays out an empirically observable trait of humans; that our opinions are primarily shaped by our intuition (emotions), not our reasoning. In other words, when we dislike something - it’s not because we came to the rational conclusion that we should - it is the other way around. We have some gut instinct either to like or dislike of something, and only if we are forced to defend our position do we start making up arguments. We let our intuition guide most of our decision making, and then let our internal press secretary (the reasoning part of our brain) explain our decisions after the fact.

Haidt calls this relationship the Rider and the Elephant. The elephant (our intuition) will mostly decide where it goes and what it does, and the rider (strategic reasoning) for the most part has to follow. To some degree, the rider can influence and actually convice the elephant to take an action against its own will - but these are rare events. This behaviour can be seen and measured when asking people to make judgment calls about things such as politics and morality.

One important aspect of our intuitive mind is that it rarely is built from rational thinking. Instead, it tends to be shaped by a combination of our genetics and our surroundings. If a person you look up to as an authority figure preaches a certain ideal, you are likely to build your own intuition around said ideal - without using any specific rational thought process.

I believe this model to be applicable to our preferences for software design patterns as well. I think the reason people decide to carve away functions and place them elsewhere is an “it feels good in my tummy” kind of situation. It looks so neat and tidy when types only have their properties, and no ugly methods to distract the reader. People then take this intuition, this aesthetic preference, and let their reasoning brain make up rhetorical talking points for why it makes sense. These talking points are then heard by large audiences (at KotlinConf), who themselves build an intuition - and the vicious cycle repeats.

Are there good uses of extension functions?

Absolutely. The most obvious case is the one even present in the name of the language feature: extension. Let us look at a simple example.

Imagine you have a module or a featureset you do not control, with some User type that has a birthDate.

// we use this, but don't control and can't change it

class User(

...

val birthDate: LocalDate

)

Now we want to have some basic business logic that checks whether or not this User is old enough to vote in elections. Let us say this requires you to be 18. In regular Java code you might be forced to do something like this:

public class UserUtil {

public static boolean isOldEnoughToVote(User user) {

var age = ChronoUnit.YEARS.between(user.getBirthDate(), LocalDate.now());

return age > 18;

}

}

// usage

public void castVote(User user, Party party) {

if (!UserUtil.isOldEnoughToVote(user)) {

throw IllegalArgumentException("Try again.");

}

...

}

But - this buries this logic check behind a Util type that one simply needs to know is there. Sure, maybe you will stumble upon it elsewhere and remember that it exists, but we can do better.

// you can also have "extension vals"

val User.isOldEnoughToVote: Boolean

get() {

val age = ChronoUnit.YEARS.between(birthDate, LocalDate.now())

return age > 18

}

// usage

fun castVote(user: User, party: Party) {

if (!user.isOldEnoughToVote) {

throw IllegalArgumentException("Try again.")

}

...

}

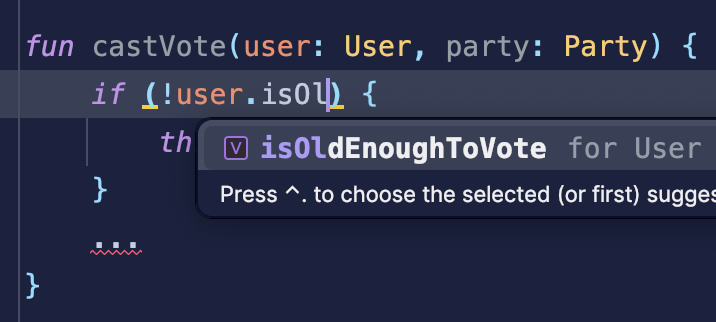

This might not look like much - but there is one pretty amazing upside. It shows up in auto completion. This successfully lets your addition be closer and thus more cohesive with the User model.

People often talk about how important it is to be able to read code, but I personally would also like to stress the importance of discovering code at all. In large codebases, it can be very difficult to make changes and improvements without finding the right existing building blocks you are meant to incorporate.

So, wait - is this a rant about Kotlin or about humans and their moral tendencies?

I honestly don’t know. There is a larger story brewing within me on the theme of developers’ emotional and intuitive connections to the tools they use. Whether frameworks, languages or patterns become popular because they rationally solve a real problem - or whether they were presented at an amazing keynote by an industry celebrity that sparks an irrational wave of inspiration.

Today it came in the form of a rant at Kotlin - one day (if ever) it might be a long post of its own.